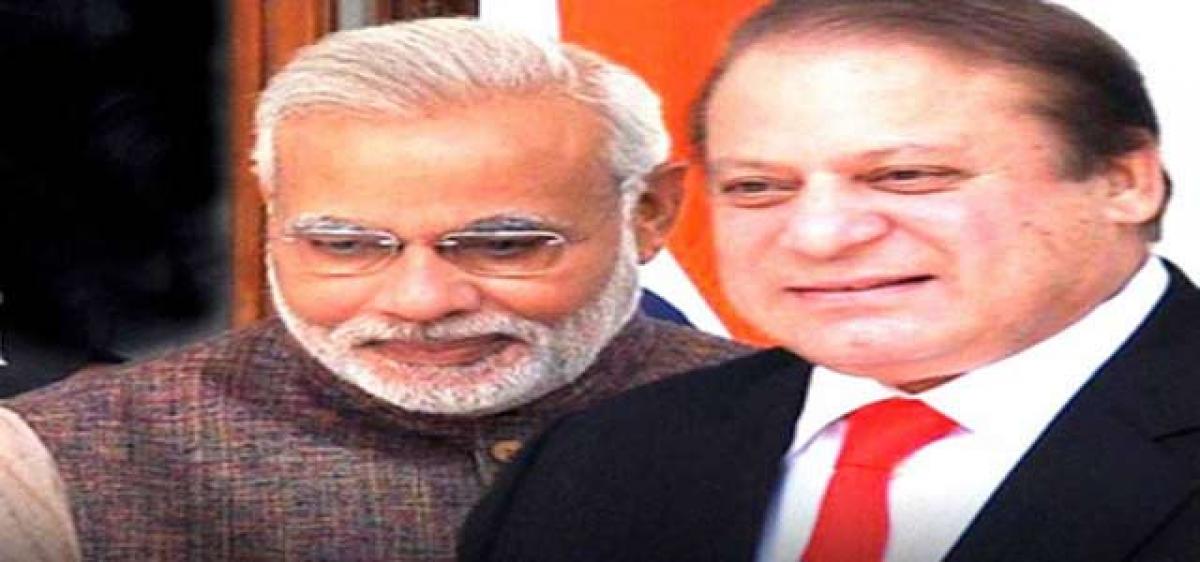

Bringing India, Pak together

Much as we in India decry lack of tolerance of ‘others’ in our separated-at-birth neighbour and perennial adversary – overlooking similar tendencies among ourselves – we should also note developments that indicate the contrary. And, perhaps, draw a lesson or two from them.

Much as we in India decry lack of tolerance of ‘others’ in our separated-at-birth neighbour and perennial adversary – overlooking similar tendencies among ourselves – we should also note developments that indicate the contrary. And, perhaps, draw a lesson or two from them.

India-Pakistan relations are destined to remain hostile. But that is no reason why people of the two nations should not try to know and understand each other.

A trend that needs noting is the effort by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to cast himself in a reformist image.

It has gladdened the hearts of the liberals at home and outside, otherwise dismayed by much that is happening in Pakistan.

On his watch, the National Assembly has enacted law according recognition and relief to religious minorities, something that was overdue by close to seven decades.

Hindus, Christians (there are more Christians than Hindus) and other miniscule minorities can register their birth, death, marriage, divorce and issues like property inheritance.

Pakistan now has a law that provides a semblance of protection of women in general. Sharif has resisted vocal opposition to it from Islamist parties, the powerful Council for Islamic Ideology (CII) and militant groups.

It may not be enough, but on both, and many more scores, he has maintained a delicate balance, despite reservations within his own party.

The going is not easy. While a right-of-centre Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) headed by the Prime Minister is bringing about these changes, the Sindh Government, run by a supposedly left-of-centre Pakistan Peoples’ Party is wavering and even stepping back.

It has decided to review the recently-passed protection of minorities bill after religious scholars objected to some of its clauses.

The bill aims at curbing forced conversions to Islam of members of minority communities. Islamic scholars have protested against the bill saying some of its clauses were unconstitutional and against Islam’s teachings.

He hopes the “civ-mil”(civil-military) equations would remain good and he has a smooth sailing. He has chosen an apparently “non-political” soldier as the new army chief Gen.

Qamar Javed Bajwa. In picking him, Nawaz has displayed reformist streak. Bajwa’s wife has relations from the Ahmediyya community that was declared non-Muslim in 1974. Islamists and sections of social media have taken a dim view of this.

A possible reason for Sharif to have gotten this far is that with no serious challenge from a fractious opposition, the most vocal being just-sound-and-fury Imran Khan, he appears to have ridden out the crisis that threatened to cut short his third term in office.

He struck a fine, even if uneasy, balance with Gen Raheel Sharif, who has just retired, and hopes to continue that with the successor.

Nawaz is indeed looking at a fresh term in 2018, but that is too far away. The current optimism could prove premature given the volatility of Pakistani politics.

A little earlier, last month, he honoured Pakistan's only Nobel laureate scientist Dr Abdus Salam by renaming the National Centre for Physics at Quaid-i-Azam University (Islamabad) as 'Professor Abdus Salam Center for Physics.'

Salam was an Ahmedi and Nawaz now risks a backlash from fundamentalists who consider the physicist a heretic.

A major figure in the 20th century theoretical physics, Salam shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics for his contribution in that field.

In 1980, soon after he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contribution to developing the theory of electroweak unification in particle physics, he was invited to a ceremony at the Quaid-e-Azam University (QAU) in Islamabad.

Few at the time expected the decision would backfire. But it did, and the reason was because of sectarian hatred unleashed by a 1974 law that declared the Ahmadi community – to which Dr Salam belonged – as non-Muslim.

Salam arrived in Islamabad to attend the ceremony, but couldn't enter the QAU premises due to fierce agitation started by student members of the powerful political and religious wing of the Jamaat-e-Islami party.

When Salam returned home on receiving the Nobel Prize, no one received him at the airport. Right wing propaganda concocted conspiracy theories to accuse him of nuclear espionage.

When he was invited to Quaid-e-Azam University for his lecture, he was threatened by the fundamentalist students.

Then President Ziaul Haq refused to endorse the candidature of Salam as a Director General of UNESCO even though Salam visited nearly 30 countries in 1987 and gained their support.

In 1988, the then Prime Minister, Benazir Bhutto, refused to meet him after making him wait for two days in a hotel. Similarly, Nawaz Sharif, in his first term of premiership, conveniently ignored Salam.

Had Salam given up his Pakistani nationality, he would have easily avoided such humiliations, but he remained a Pakistani national until his last breath.

The Ahmadi movement has its origins in British-India in the late 19th Century. The community takes its name from its founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who was born in 1835 and was regarded by his followers as the Messiah and a prophet.

Although its members follow the teachings of the Koran, they are regarded by orthodox Muslims as heretical because they do not believe that Mohammad was the final prophet.

In 1974, under severe pressure from clerics, Pakistan's first elected Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto introduced a constitutional amendment - known as the second amendment - which declared Ahmadis as non-Muslims.

A decade later, a new law was brought in barring Ahmadis from calling their places of worship mosques or from propagating their faith in "any way, directly or indirectly."

Described by rights organisations as one of the most relentlessly persecuted communities in Pakistan, the Ahmadis have seen their personal and political rights deteriorate steadily over the years.

Even as this is being written, Ahmedi shrines are being attacked and the community members are leaving their homes in Chakwal out of fear.

Yet another development bags attention. Revoking an earlier ban, The Pakistan National Council of Arts (PNCA) permitted the Ajoka Theatre Pakistan to perform on December 14 “Kabira Khara Bazaar Mein,” the celebrated play of Bhisham Sahni.

Touching on the Bhakti movement, the play touches upon the Sufi mystic and sheds light on the problems Kabir faced when he challenged the mullahs and pundits with equal zeal.

The play shows Kabir being attacked by the Hindu and the Muslim religious establishment but enjoys the undying love of the people.

The play had performed to packed house in Lahore before being banned by PNCA that had then believed the play promoted intolerance.

“It’s an amazing script with a positive message and I cannot think of any reason why the previous PNCA management was so apprehensive,” says Jamal Shah, the present PNCA director general.

Finally, take the debate over the ban on Indian films in retaliation to the decision at the India end to ban Pakistani artists in Bollywood films.

The debate, at least in the English language press and even though it represents only a section of the intelligentsia, is not one-sided on the government’s recent kneejerk decision to ban all Indian content in response to India’s ban on Pakistani talent.

Taimur Tajik writes in Herald magazine: “Whether we admit it or not, the majority of Pakistanis are head-over-heels for Bollywood. We laugh and cry at their films, we marry to their music and we gush and gossip over their celebrities as if they were our own.

And why not? Bollywood is a force to be reckoned with. It is glamorous, sultry, hot, sweaty, rambunctious - and most of all downright entertaining.

And as a nation, we are absolutely addicted. This is why it made me wonder that by banning Indian content from Pakistan, who are we really punishing? India? Bollywood? Or are we really just ourselves?”

Indians are yet to seriously review their decision, taken under the threat of Shiv Sena and Maharashtra Navnirman Sena amidst tense bilateral relations over terror attacks emanating from Pakistani soil.

But the Pakistan film industry was doing – for a different set of reasons that centre on their economic viability and even survival.

The Pakistanis finally revoked the ban at their end and it would be in fitness of things and that sooner than later, India too follows it. That would augur well for both.