Bangladesh's Government Fails To Solve Arsenic Problem In Drinking Water

Human Rights Watch denounces Bangladesh\'s government inability to solve the water problem in the rural areas of the country. Yet the problem has been well known since 1990\'s.

Human Rights Watch denounces Bangladesh's government inability to solve the water problem in the rural areas of the country. Yet the problem has been well known since 1990's.

In his mid-30s, Khobor recently noticed patchy marks across his chest and on his feet. His mother died three years ago and his father a year later, both with similar but more pronounced marks on their bodies.

Khobor suspects these marks are caused by arsenic in water from the family’s nearby tubewell, a small diameter pipe drilled into the ground that allows him to draw up water by a hand pump. When the government tested water from the tubewell many years ago they told him the water had around “250 [micrograms per liter] arsenic.” The family has no alternative but to drink from the contaminated well. Still, he knows what that means: “[The water] can kill us.”

There is a serious lack of monitoring and quality control in arsenic mitigation projects. In a small but significant number of cases, government-installed water points are themselves contaminated with arsenic above the national standard. Human Rights Watch visited one village where some contaminated government-installed wells were used by villagers as a source of drinking water. According to Human Rights Watch’s analysis of approximately 125,000 government water points installed between 2006 and 2012 (constituting most government water points installed in this period), some 5 percent were contaminated above the Bangladesh standard.

Today, an estimated 43,000 people die each year from arsenic-related illness in Bangladesh, according to one study. The authors go on to estimate that, depending on progress of ending exposure, between 1 and 5 million of the 90 million children estimated to be born between 2000 and 2030 will eventually die due to exposure to arsenic in drinking water.

It finds that the official response to arsenic contamination of drinking water in Bangladesh’s rural villages is failing, with the government instead expending considerable resources in areas where the risk of arsenic contamination is relatively low and where water coverage is relatively good. Despite government reports stating that the government should do a better job of targeting arsenic mitigation options in areas where they are most needed, it inexplicably fails to do so. Human Rights Watch wrote to the government to ask the reason for this approach, but no reply had been received at time of publication.

Balish, in his mid-60s, works as a farmer and also lives in Bilmamudpur village. There are six people in his household. He has dark spots across his chest and the backs of his hands, and thick skin on the palms of his hands. He told Human Rights Watch that three people in his household had died of arsenic-related problems about 10 years ago, with spots on their bodies and feet that he described as swollen and cracked. He recalls that an NGO had tested his household’s tubewell in about 2006 and told him it contained 450 micrograms of arsenic per liter of water.

Under the World Bank’s Bangladesh Water Supply Program Project (BWSPP) (2004-2010) some 13,000 rural water points were installed by the government with the bank’s support. Human Rights Watch has no indication that water points installed by the government with World Bank support were contaminated with arsenic.

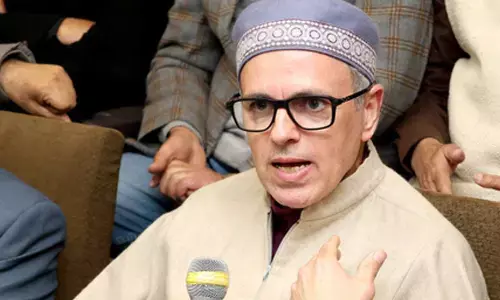

The governments wells that are contaminated desperately need to be replaced before people lose the little faith they have in the government's capacity to provide for sane water, says Human Rights Watch reporter Richard Pearshouse.