Scientists unlock secrets of a sixth basic flavour

Share :

US scientists have found evidence of a sixth basic taste - umami - in addition to sweet, sour, salty and bitter, eight decades after Japanese scientist Kikunae Ikeda first proposed it in the early 1900s.

New Delhi: US scientists have found evidence of a sixth basic taste - umami - in addition to sweet, sour, salty and bitter, eight decades after Japanese scientist Kikunae Ikeda first proposed it in the early 1900s.

Researchers at the University of Southern California-Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences have found that the tongue responds to ammonium chloride through the same protein receptor that signals sour taste.

Emily Liman, Professor of biological sciences speculates that the ability to taste ammonium chloride might have evolved to help organisms avoid eating harmful biological substances that have high concentrations of ammonium.

"Ammonium is found in waste products -- think of fertiliser -- and is somewhat toxic, so it makes sense we evolved taste mechanisms to detect it,” she said, in the paper published in the journal Nature Communications.

In some northern European countries, salt licorice has been a popular candy at least since the early 20th century. The treat counts among its ingredients salmiak salt, or ammonium chloride.

Scientists have for decades recognised that the tongue responds strongly to ammonium chloride. However, despite extensive research, the specific tongue receptors that react to it remained elusive.

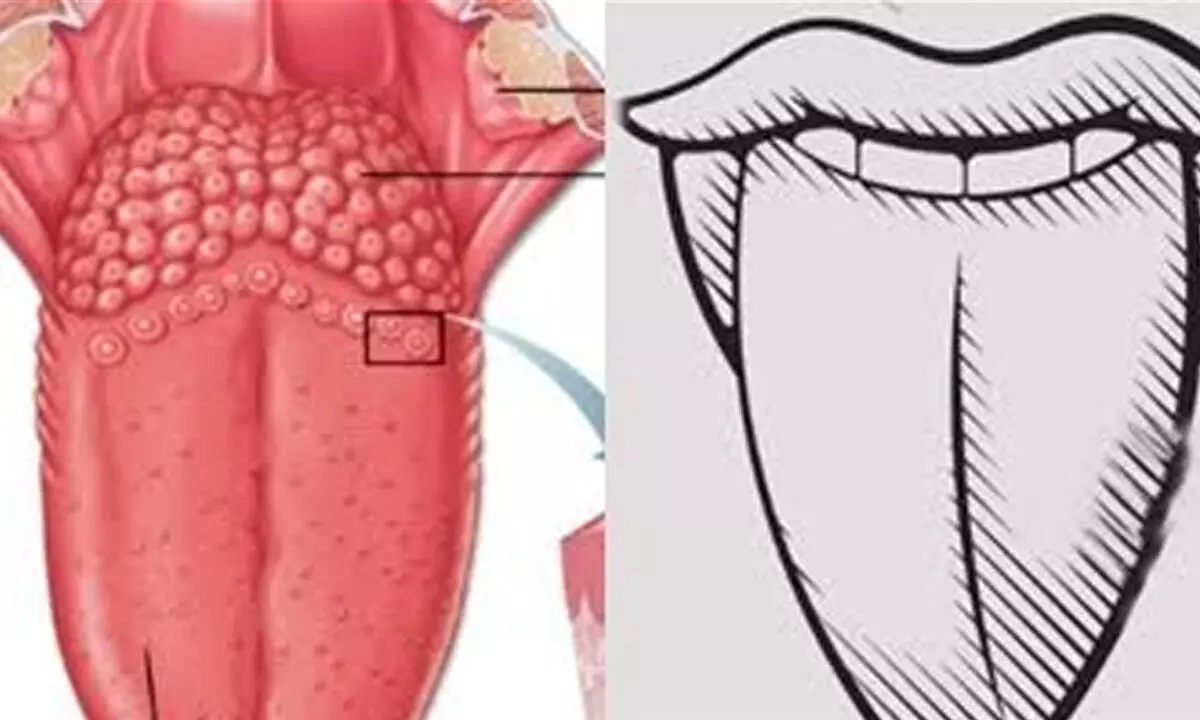

In recent years, the scientists have uncovered the protein responsible for detecting sour taste. That protein, called OTOP1, sits within cell membranes and forms a channel for hydrogen ions moving into the cell.

Hydrogen ions are the key component of acids, and as foodies everywhere know, the tongue senses acid as sour. That's why lemonade (rich in citric and ascorbic acids), vinegar (acetic acid) and other acidic foods impart a zing of tartness when they hit the tongue.

They introduced the Otop1 gene into lab-grown human cells so the cells produce the OTOP1 receptor protein. They then exposed the cells to acid or to ammonium chloride and measured the responses.