A historical perspective

The past provides us with a lens through which we decipher the present and relate to events around us. Historical research, fiction, memoirs and discussions that dwell on the past become necessary to commemorate events like wars, victories, mergers or separation.

The past provides us with a lens through which we decipher the present and relate to events around us. Historical research, fiction, memoirs and discussions that dwell on the past become necessary to commemorate events like wars, victories, mergers or separation.

The past is never laid to rest but lingers on through different narratives and perceptions. Come September and Hyderabad witnesses a recap of events related to the significance of September17, 1948, a year that remains etched in gold in the history of this cosmopolitan and forward-thinking city. New book releases, divergent views on the nomenclature used to describe the day and disdain over distorted history never fail to kick up controversies each year.

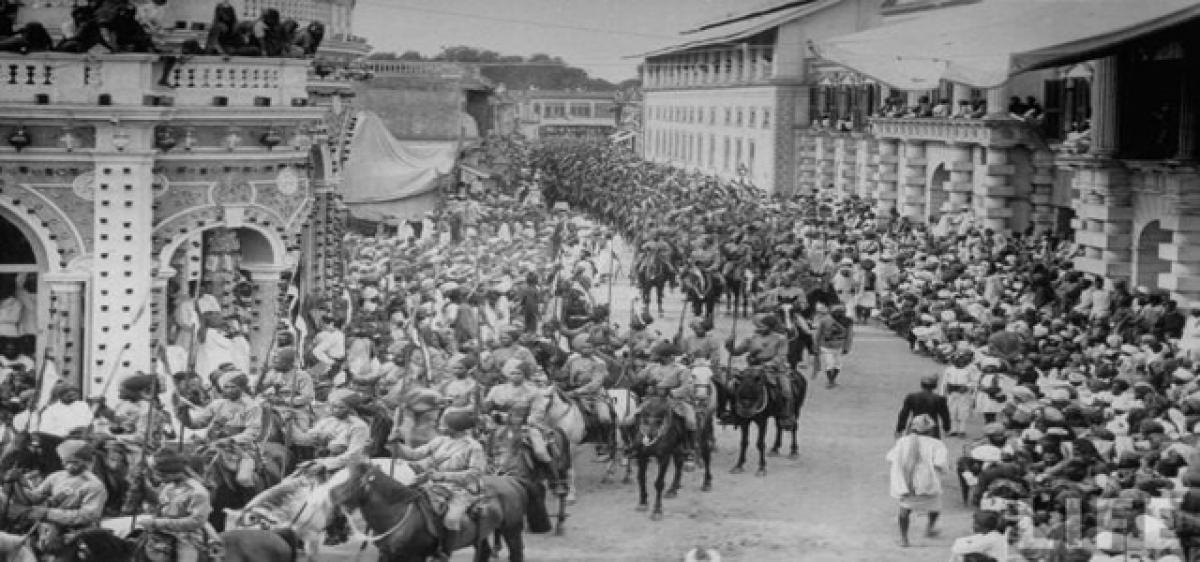

The five-day September operation with code names like ‘Operation Polo’ and ‘Operation Caterpillar’ better known as ‘Police action’ brought the curtains down on the writ of the Nizam, who held sway over the region for 37 years.

The political climate and series of events in the Princely State of Hyderabad ruled by the then richest man in the world, and the final merger of his dominion with the rest of independent India make a fascinating study, providing insights into the social, political and geographical milieu of the pre-independence struggle.

This was a period of great turmoil, where large cross sections of society were at strife with the powers that be. The Congress, the Arya Samajis and the Communists were all waging a struggle to end the feudal system that ruined the rural landscape and liberate Hyderabad from the clutches of the Nizam.

Their mode of protests may have been different but their goal was common. At the other end of the spectrum was an administration led by the 7th Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, who believed that he was the saviour of the masses, born to rule, enjoyed British protection and presided over an independent sovereign State.

Mohammed Hyder, a civil servant, who served as collector of Osmanabad (now in Maharashtra) during this period, in his book ‘October Coup’, a memoir of the struggle for Hyderabad, explains the situation in the following words. “Hyderabad was predominantly Hindu with Muslims representing some 20 per cent of the population.

From one perspective its political arrangements were self-evidently undemocratic with an autocratic Muslim ruler at the head of the system and a small apparently reactionary Muslim ruling class dominating its administration and political life.”

The remarkably contrasting view of the Nizam being a benevolent, secular ruler with an excellent administration and ruling elite is also presented in the same vein - The establishment of a university, a public library, railway lines and industries, placing railway and road transport in the public sector and several other initiatives undertaken to support this viewpoint.

The Nizam remained the highest ranking Prince in India entitled to a 21 gun salute, was referred to as ‘His Exalted Highness’ and was a ‘faithful ally of the British crown after World War I, owing to his financial contribution to the British empire’s war effort.

The nature of land ownership in the region ruled by him was however extremely exploitative. About 40 per cent of the land was directly owned by the Nizam or given by him to the elites as Jagirs (special tenures). The remaining 60 per cent was under the land revenue system of the government, which relied on powerful Zamindars (landlords) with no legal rights or security from eviction to the actual cultivators.

The vetti (bonded labour) system under which people from the lower castes worked in the household and farms at the will of the landlord, the practice of sending girls as slaves to their houses to be used as concubines, and collection of produce as levy from poor farmers made them defenceless and deprived them of a life of dignity. The instant greeting of submissive welcome by the poor farmers, “Banchanu Dora” (I am your slave) reflected the extreme depravity of the landed class, whose tales of inhuman behaviour abound in the region.

The killing of Doddi Komariah, a member of the Andhra Mahasabha in 1946 sparked a rebellion against the landlords, who colluded with the Nizam’s police, henchmen and the Razakars, a newly formed fundamentalist militia of the Majlis- Ittehadul- Muslimeen (MIM) in suppressing the peasantry. “Land for the Tiller” became the new slogan and Landlords were driven out of their palatial ‘gadis’ (bungalows).

The communist-led movement gradually gained strength and assumed the character of a national liberation struggle to end the misrule of the Nizam and the hegemony of the feudal lords. Ampasayya Naveen’s Sahitya Akademi award winning book ’Kaalarekhalu’ (Imprints of time) traces atrocities like murder, rape, arson and looting unleashed by notorious landlords like Visnoor Zamindar Ramachandra Reddy, the emergence of communists as protectors fighting the Razakars , and the integration of Hyderabad with India after the courageous intervention ordered by India’s first home minister Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel. It also narrates the plight of women, who bore the brunt of the attacks and tied chilli powder around their waists to save their honour.

Noted communist leader Puchalapalli Sundarayya in his book ‘Telangana: People’s struggle and its lessons’, talks about the enormous support that the communist guerrilla squads received from the men and women of the villages united in their fight against a cruel regime. Razakars, who had their centres in huge cities and towns used to raid villages, loot the people and pull down the national and red flags.

They had spears, jambias, swords, muzzle loaders and rifles with them whenever they made these raids. One thing must be noted here that just as in the earlier period, the people both Hindus and Muslims, had fought in the villages against the landlords unitedly, so also they fought shoulder to shoulder against the Razakars without falling prey to religious fanaticism’.

“Bandenka, bandi katti padahaaru bandlu katti” (In your convoy of 16 vehicles, where will you be hiding, as we prepare to dig your grave, O Nizam?) was one of the many popular songs that resounded in the villages and enthused people in their fight against the Nizam.

‘India is a geographic notion. Hyderabad is a political reality. Are we prepared to sacrifice the reality of Hyderabad for the idea of India?’ the documented response of Qasim Razvi, to a question about the future of Hyderabad depicts the intentions of the man, who gained notoriety for sowing the seeds of communal divide in Hyderabad.

This small time lawyer from Latur, who emerged as an important leader of MIM and led the fundamentalist militia of armed Razakars (volunteers), had no qualms about killing journalist Shoebullah Khan, a fellow Muslim, who exposed the atrocities of the Razakars and police through his paper ‘Imroz’. Not only was he shot down but his arm cruelly cut as an act of revenge.

Maqdoom Moinuddin, a blithe spirit, romantic and revolutionary poet, who strayed into politics as a communist party worker was vocal in his criticism of the oppressive rule of the Nizam and was jailed for trade union activities several times. He was one of the many progressive voices that denounced the activities of fundamentalists surrounding the Nizam.

The paramilitary wing created by Razvi organised on the model of the “Brown Shirts” of Hitler had to take a pledge that they would sacrifice their life for the party and fight till the very end to maintain Muslim power in the State. They were armed with a variety of weapons that included swords, spears, .303 bore rifles and muzzle-loading guns.

Former bureaucrat and historian Narendra Luther in his book ‘Hyderabad - A Biography’ says, “It was widely believed that Razvi had the blessings of the Nizam, though in the later period he began to dictate terms even to him. He enjoyed the material and financial support of the government and leading industrialists like Laik Ali, Ahmed Alladin and Babu Khan, who gave liberal financial help to the Ittehad and to Razvi.”

“Razvi promised his followers that the waters of the Bay of Bengal would kiss the feet of the Nizam and that the Asafia flag would be planted on the ramparts of the Red Fort at Delhi,” he adds.

When the British departed from India in 1947, they gave the Princely States the option of acceding to either India or Pakistan or staying as an independent State. In March 1947, Lord Mountbatten arrived in India with the mandate of granting freedom to the country. The Nizam had declared that he would neither join India nor Pakistan (after realising that joining Pakistan would not be possible) but would remain independent.

A decision to sign the ‘standstill agreement” between Hyderabad and the Indian Union, which spoke of maintaining the status quo of the Princely State of Hyderabad for one year during which no military action would be taken, was opposed by Razvi, who staged a demonstration in front of the houses of the Prime Minister, Nawab of Chattari, advisor Sir Walter Monckton, and minister Nawab Ali Nawaz Jung, the main negotiators of the agreement. After many developments and the appointment of Laik Ali as Prime Minister in place of Chhattari, the agreement was signed in November 1947.

The Nizam’s ill-advised decision to take the Hyderabad dispute to the United Nations, banning Indian currency in the State, engaging an Australian gun runner in smuggling arms into Hyderabad and sanctioning of a 200 million loan to Pakistan, were a breach of the ‘standstill’ agreement and hostile acts intended to provoke Delhi.

A report about the increasing atrocities of the Razakars and the fact that the Nizam would neither accede to India nor introduce a responsible government in the state became increasingly clear and the centre was forced to act. Maj Gen J Chaudhuri-led the military operation to victory and Hyderabad became a part of India. The action had its dark moments too.

There were reports of arson, looting and reprisal killing of Muslims and communists with the Sunderland committee appointed by Nehru putting the number anywhere between 27, 000 to 40,000. There was, however, a feeling of relief that an autocratic rule that wanted to align with forces not acceptable to a majority of the people had at last come to an end. It was a victory against an unacceptable regime devoid of communal feelings. Nationalistic fervour gripped the people and an air of festivity enveloped the city and surrounding areas.

The shouting rampaging crowds of Razaakars had disappeared and the streets of Hyderabad were a sea of humanity with people of all ages coming out waving the tricolour. ‘Quami nara’ (The slogan of the land)... a shrill lone voice shouted and the mob replied in unison ‘Jai Hind’. The city built on the foundation of love resonated with patriotic fervour and the pride of belongingness. History does have its bright moments and invaluable lessons.

The article is based on extracts from ‘Hyderabad - A Biography’ by Narendra Luther; ‘Kaalarekhalu’ by Ampasayya Naveen, ‘October Coup’ by Mohammed Hyder’; ‘Telangana: People’s Struggle and its Lessons’ by Puchalapalli Sundarayya