Also for your eyes only

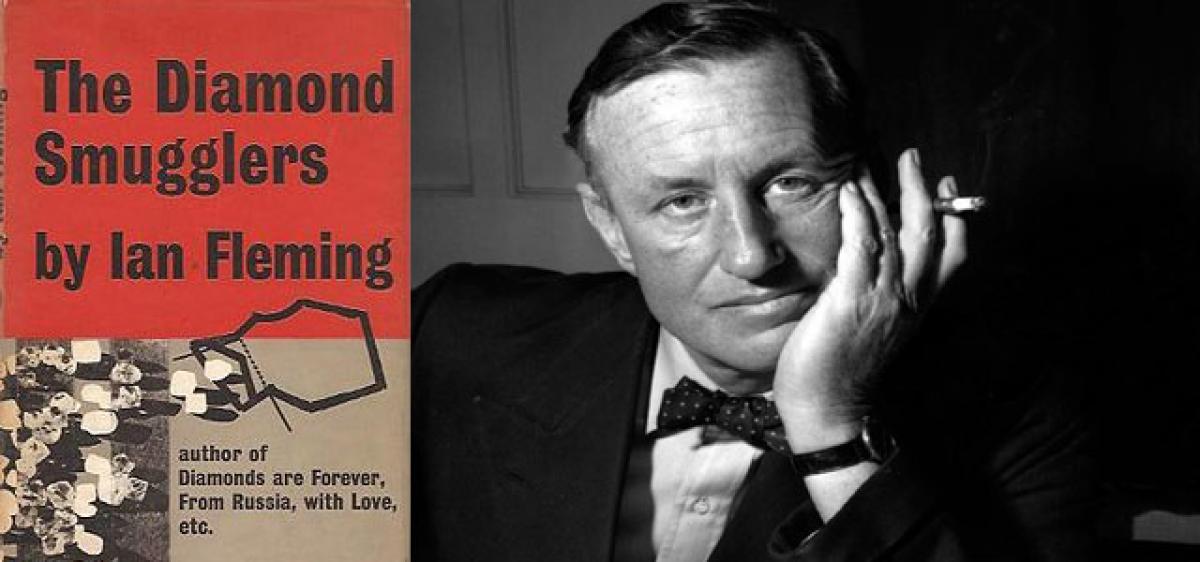

His name is synonymous with the exploits of the most famous, though fictional, secret agent ever, but apart from this irresistible mixture of fantasies expertly served – and a last-ditch demonstration of British power – Ian Fleming had other literary skills up his sleeve. Unfortunately, he had very limited time and opportunity to exhibit them.

His name is synonymous with the exploits of the most famous, though fictional, secret agent ever, but apart from this irresistible mixture of fantasies expertly served – and a last-ditch demonstration of British power – Ian Fleming had other literary skills up his sleeve. Unfortunately, he had very limited time and opportunity to exhibit them.

Largely overshadowed by the 12 James Bond novels and two short story collections, are three works spanning a remarkable range of genres – from a magical tale for children to an entertainingly opinionated travelogue that revealed another side of Fleming.

A journalist, stockbroker and naval intelligence officer before returning to journalism after World War II, Fleming (1908-64) became widely known after ‘Casino Royale’, the first of the Bond adventures, was published in 1953. However, he didn't let 007 take over his entire creativity.

While the Bond books are more plausible (and much darker) than the glamorous, high-tech screen adaptations, they were well researched by Fleming. And it was this aspect, which led to his first non-fiction work.

Foreign Manager in the Kemsley newspaper group, which then time owned The Sunday Times, and overseeing the paper's network of foreign correspondents, he became interested in the smuggling of diamonds from Africa after reading a news story on the issue. Though most of his research was for the fourth Bond novel ‘Diamonds are Forever’ (1956), he also used it for ‘The Diamond Smugglers’ (1957).

"One day in April 1957, I had just answered a letter from an expert in unarmed combat writing from a cover address in Mexico City, and I was thanking a fan in Chile, when my telephone rang..." it begins and goes on to tell about the work of the International Diamond Security Organisation (IDSO), then headed by an ex-chief of Britain's MI5.

Based on two weeks of interviews (in Tangier) of ex-security service agent and IDSO operative John Collard (referred to as 'John Blaize' and described as a "reluctant hero, like all Britain's best secret agents"), the book, however, suffered from Fleming not visiting the African areas in question, Collard cutting out his literary flourishes, some matter being already known, and a large chunk being left out at De Beers' insistence.

Fleming himself was not too fond of it. As Fergus Fleming notes in his foreword to the Vintage edition, in the inscription of his personal library copy, his uncle termed it "...adequate journalism but a poor book and necessarily rather contrived though the facts are true". However, Fergus Fleming argues that despite perching uncomfortably between two genres, it has its touches, especially the "strange" interview of Collard on a jellyfish-strewn beach on the very tip of Africa.

Receiving a mixed response, it however was then commercially most valuable, selling in the hundreds of thousands, and nearly becoming the first of his works to be filmed.

Fleming was better pleased with ‘Thrilling Cities’, bringing, in his own words, a "thriller writer's view" of some major cities. It was based on a series of articles he wrote for The Sunday Times on two extended trips -- the first around the world in 1959, and then driving around Europe in 1960.

Suggested by a colleague that he take a five-week, all-expenses-paid trip around the world for a series of features, Fleming had initially declined terming himself a terrible tourist who "often advocated the provision of roller-skates at the door of museums and art galleries" but was ultimately persuaded by the contention that he could also get some material for the Bond books in the process.

The first trip included Hong Kong (with brief vignettes of stopovers in Beirut, New Delhi and Bangkok), Macau (where he investigated the gold trade), Tokyo, Honolulu, Los Angeles and Las Vegas (in one chapter), Chicago, and New York (which received a rather jaundiced view due to his tiredness) -- all in the terse, subjective (though still cleverly incisive) and cynically jaded tones we are familiar from the Bond books.

It also grew exciting when his plane nearly crashed between Japan and Hawaii after engine failure.

Sunday Times chairman Roy Thomson enjoyed Fleming's articles and suggested a number of other cities but the follow up was Fleming's drive through Hamburg (where he visited the red-light district), Berlin, Vienna, Geneva (with accounts of current scandals), Naples (where Lucky Luciano came to tea) and Monte Carlo (and its casinos).

Fleming's final non-Bond book was based on the bedtime stories he told his son, Caspar. Recuperating after a series of heart attacks following the ‘Thunderball’ case, he was persuaded to turn them into a book. This was ‘Chitty-Chitty Bang Bang’, published a few months after his death.

Also adapted into a film, which changed the rather basic plot to near-fantasy though introducing Bond-like heroines (Truly Scrumptious), it was testament to Fleming's skill at storytelling for all ages – and that the child in all of us never grows up fully.