Live

- Officials told to work in coordination for smooth conduct of Group-2 exams

- Alliance, YSRCP corporators argue over expensive projects

- New CMR mall opens in Kurnool

- Former Speaker Tammineni’s clout on the wane

- Attack on media: Take action against Mohan Babu, demand journalists

- More sports equipment promised at Central Park

- Mohan Babu’s attack on journalists inhumane act

- West Quay-6 of VPA to get revamped

- Rajaiah demands govt to introduce SC categorisation Bill in Assembly

- Make all arrangements for smooth conduct of Group-2 exams

Just In

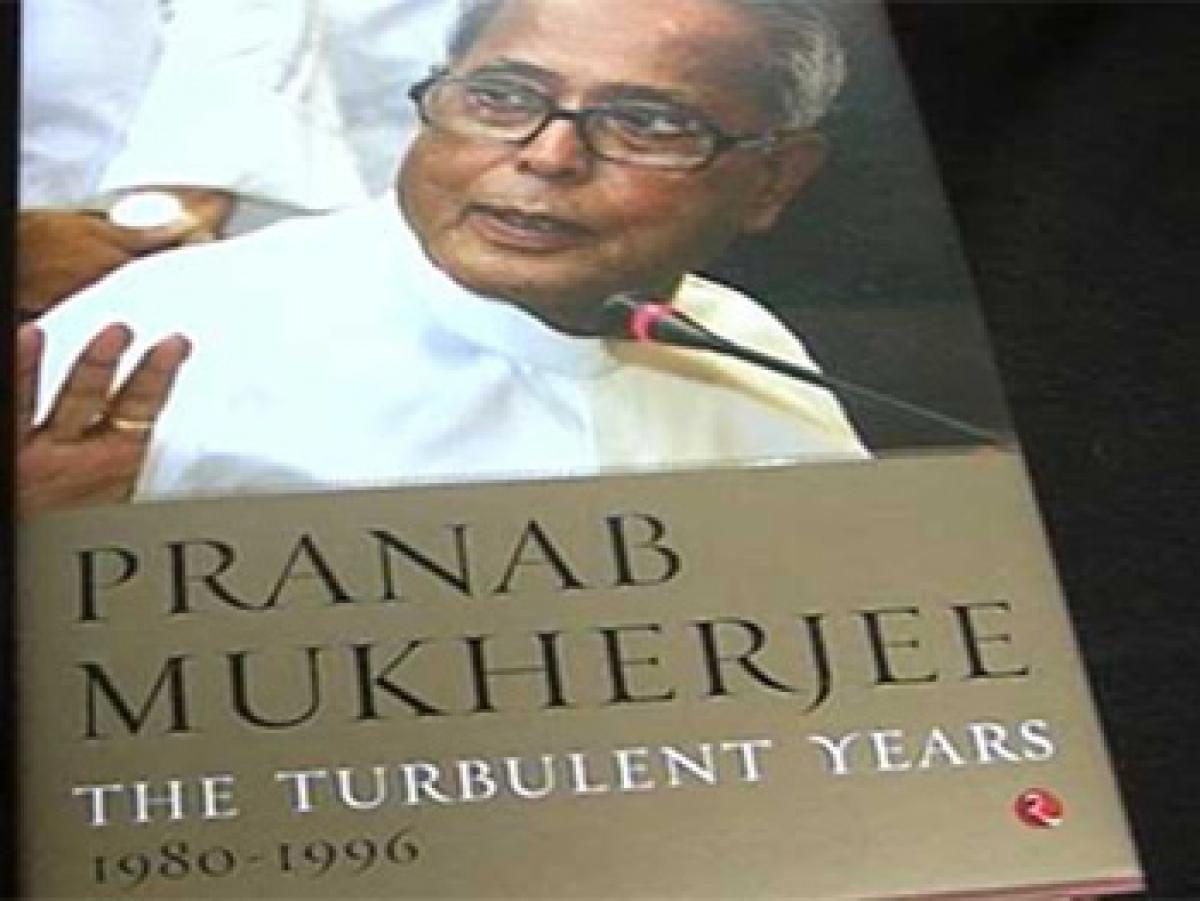

One thing that can be said without any doubt or ambiguity about the second volume of President Pranab Mukherjee’s memoirs is that he reflects the views of all right-thinking people on an array of major events in times that were full of controversies.

The title “The Turbulent Years: 1980-96” is most appropriate of that period that remains etched in the memory of those of us who were 20-plus then. We now have an insider’s view of those events, coming from a man who held key positions at the top. While some officials have told their stories, Pranab Mukherjee is, perhaps, the only politician of that era to record his version. And since he must cover the remaining period at least till he became the President, a third volume to cover the last lap of 17 or 18 years is most likely

One thing that can be said without any doubt or ambiguity about the second volume of President Pranab Mukherjee’s memoirs is that he reflects the views of all right-thinking people on an array of major events in times that were full of controversies.

Views may differ in a democracy, but nobody can challenge the right of a citizen, from President to pauper, to express views. He may be accused of telling his side of the story. He may have been selective. But on both these counts, he has exercised his right. In doing so, Mukherjee has become the first Head of State to write his memoirs from the precincts of the Rashtrapati Bhavan.

The title “The Turbulent Years: 1980-96” is most appropriate of that period that remains etched in the memory of those of us who were 20-plus then. We now have an insider’s view of those events, coming from a man who held key positions at the top.

While some officials have told their stories, Mukherjee is, perhaps, the only politician of that era to record his version. And since he must cover the remaining period at least till he became the President, a third volume to cover the last lap of 17 or 18 years is most likely.

Writing memoirs is rare by politicians in India. When they are holding office, they are shy and wary of letting out official secrets and when not in power, they are waiting for a chance to get back. Indeed, it is a never-ending wait well into the evening of their lives. Some have used their retirement, forced or voluntary, to reminsce or to settle old scores.

As for the President, with quite a few exceptions though, given supreme, but limited powers, he/she is not always in good books of the government of the day. Clashes of egos and perceptions characterised the relationship between an all-powerful Jawaharlal Nehru and Rajendra Prasad and S Radhakrishnan. But the two never crossed the Lakshman Rekha drawn by the Constitution.

Problems are inevitable if the government happens to be of a different political ideology than that of the President. Much is left unsaid, as decorum is maintained by all concerned, but tensions simmer. Thus it was that Giani Zail Singh was totally ill-at-ease after the Operation Blue Star in 1984 about which Mukherjee dwells in great detail, and with Rajiv Gandhi. K R Narayanan did not conceal his concern at the way Gujarat’s sectarian violence of 2002 was handled.

On his part, Mukherjee has expressed himself several times against the sectarian approach of the ruling party and the ambience of intolerance of the current times. But it needs stressing that like his predecessors he has been graceful, expressing his views without rancour. One may agree or disagree with his views, but he cannot be accused of being partisan. And this is saying something about a person who began as a grass-root political worker and rose in ranks over six decades in public life.

His career saw numerous ups and downs. Providence also played its role. He had lost the 1980 Lok Sabha polls and stood little chance of being in the government. A mere attendee at the Rashtrapati Bhavan when Indira Gandhi and her government were being sworn in, he was suddenly called to take the oath of office.

The reason was that Mrs Gandhi had decided on 24 ministers in her team. One of them, Bhagwat Jha Azad, was apparently unhappy at being tipped to be a Minister of State. He had walked out minutes before the President arrived.

In the next two years, Mukherjee came to head Commerce and then Finance Ministry and was designated Number Two, to preside over cabinet meetings in Mrs Gandhi’s absence. No other minister has had such a quick rise. And that proved to be his undoing.

The most important part of this volume is his clarifying in great details that he never sought to be the Prime Minister. He tells you that he had rejected the suggestion of the then Cabinet Secretary, Krishnaswamy Raosaheb, that following the precedence of Gulzari Lal Nanda, Mukherjee should take oath as the caretaker Prime Minister.

Mukherjee says he shot down the idea, clearly telling that Rajiv would be sworn in as “full-fledged” premier. But the damage had been done. I recall it began with an official who perhaps saw himself serving the caretaker PM in a key position. Tongues started wagging. Mukherjee attributes this to ‘detractors’ and was “shocked and flabbergasted” at being dropped from the government, observes that Rajiv had been gullible.

The young PM, whom he had assured, “yes, you can do it” had been surrounded by people some of whom, he says, later proved to be “time servers.” He may have used mild words in keeping with the office he holds, but Mukherjee has been clear about what he has to say. The opening of Ram Janmabhoomi temple site in Ayodhya was Rajiv’s “error of judgment”.

Rajiv had also erred in reversing the Shahbanu verdict of the Supreme Court by passing a law that was regressive. An in-experienced Rajiv had pandered to the conservatives among both the Hindus and the Muslims, thus falling between the two stools. A natural outcome of this was the demolition of Babri Masjid. Mukherjee calls it an act of “absolute perfidy” that destroyed India’s image.

“The demolition of Babri Masjid was an act of absolute perfidy…It was the senseless, wanton destruction of a religious structure, purely to serve political ends. It deeply wounded the sentiments of the Muslim community in India and abroad. It destroyed India’s image as a tolerant, pluralistic nation,” he says.

He is likely to be criticised for writing this, although he doesn’t name names so far as the BJP, Shiv Sena and others. One might say he has been selective in his criticism in that he has spared them, while criticising his own government and the then PM P V Narasimha Rao, calling it his “biggest failure”. He chided Rao, raising his voice, for letting it happen. Having done that, Mukherjee recalls seeing the pain on Rao’s otherwise inscrutable face – which is saying a lot by one graceful man about another.

Mukherjee is perceptive about how implementing Mandal Commission “contributed to reducing social injustice in society, though it also divided and polarised different sections of our population”. The reservation issue has only exacerbated since then, the latest manifestation being violent agitation by the Kapus.

Mukherjee was not destined to be the Prime Minister. He has been described as the “best Prime Minister India never had.” He was supposed to have lost it when the Congress won the 1991 polls in the wake of Rajiv’s assassination.

If Jayaram Ramesh and reports of that era are to be believed, Sonia Gandhi preferred an older, sedate Rao to him. In 2014 again, she preferred Manmohan Singh, the man Mukherjee, as Finance Minister in the 1980s, had appointed Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. These are but ifs and buts of history.

A history teacher by training and a practitioner of political science, one can assume that Mukherjee will deal with how Manmohan Singh ran the country with equal equanimity, the graft, the scams, the charge of policy paralyses and much more. He was a powerful minister till he got elected the President. For, he is an authentic chronicler of the last half a century India and Indians have lived through.

© 2024 Hyderabad Media House Limited/The Hans India. All rights reserved. Powered by hocalwire.com