IIIT Hyderabad study exposes disparities in judicial sentencing

Public dataset aims to promote transparency, accountability and reform in judiciary

A groundbreaking study by researchers at IIIT Hyderabad, in collaboration with NALSAR University, has revealed troubling inconsistencies in India’s judicial sentencing patterns. By applying advanced data analytics tools, the team uncovered disparities in fines and prison terms across states, raising questions about fairness in the justice delivery system.

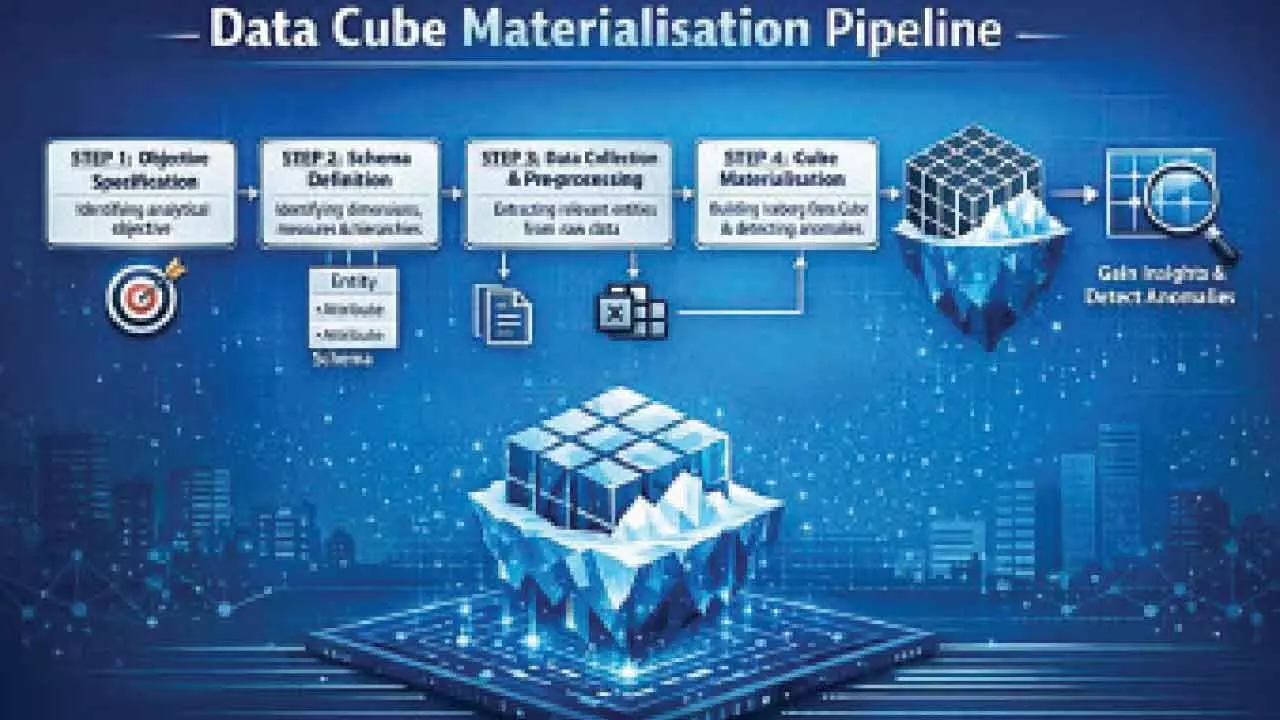

The research, titled ‘Data Cube for Exploring Anomalies in Justice Delivery: An Experiment on Indian Judgements’, was conducted by Sriharshitha Bondugula, Prof Krishna Reddy P and Narendra Babu Unnam, alongside Prof Santhy KVK of NALSAR. Their work emphasises that while judicial discretion is inevitable, unchecked variations can erode public trust in the legal system.

Judges, like all decision-makers, bring personal experiences, cognitive processes, and contextual interpretations into their rulings. This subjectivity, though human, often results in unequal treatment of similar cases. Custody arrangements, bail decisions, and sentencing outcomes can vary significantly depending on the presiding judge, resulting in disparities that directly impact the liberty and justice of individuals.

To systematically study these differences, the researchers employed Online Analytical Processing (OLAP), a technique commonly used in healthcare and marketing to analyse large datasets. Court judgments, however, are not structured like business data. To overcome this, the team manually extracted information from nearly 3,500 criminal cases involving murder, kidnapping and rape between 2005 and 2010. They then used large language models (LLMs) to convert unstructured legal text into structured datasets, capturing verdicts, punishment types, prison durations, and fines.

The results were striking. In homicide cases, fines were rarely imposed across most states, but Kerala stood out with significantly higher fine amounts and greater variation. In aggravated rape cases, Himachal Pradesh imposed higher fines compared to Delhi, despite similar averages elsewhere. For aggravated kidnapping, Rajasthan handed down longer prison terms than Haryana. These findings highlight how sentencing outcomes can diverge sharply depending on geography, even for similar crimes.

The study underscores the tension between judicial discretion and consistency. While flexibility allows judges to tailor sentences to individual circumstances, excessive variation risks undermining fairness. The researchers point to international parallels, such as the United States, where sentencing guidelines introduced in the 1980s sought to reduce subjectivity but sparked debates about rigidity versus justice.

By making their dataset--the Indian Judgements Punishment Data (IJPD--publicly available, the team hopes to encourage further exploration of disparities in judicial decisions. Plans of the future include extracting data directly from full judgment texts and incorporating additional dimensions such as the age of the accused, the victim’s age, and even the judge’s gender.

Ultimately, the study offers a powerful reminder: while data cannot replace human judgment, it can illuminate where discretion begins to resemble disparity. In a system built on fairness, such insights are crucial for fostering consistency, accountability, and public trust in the judiciary.