A never ending Saga

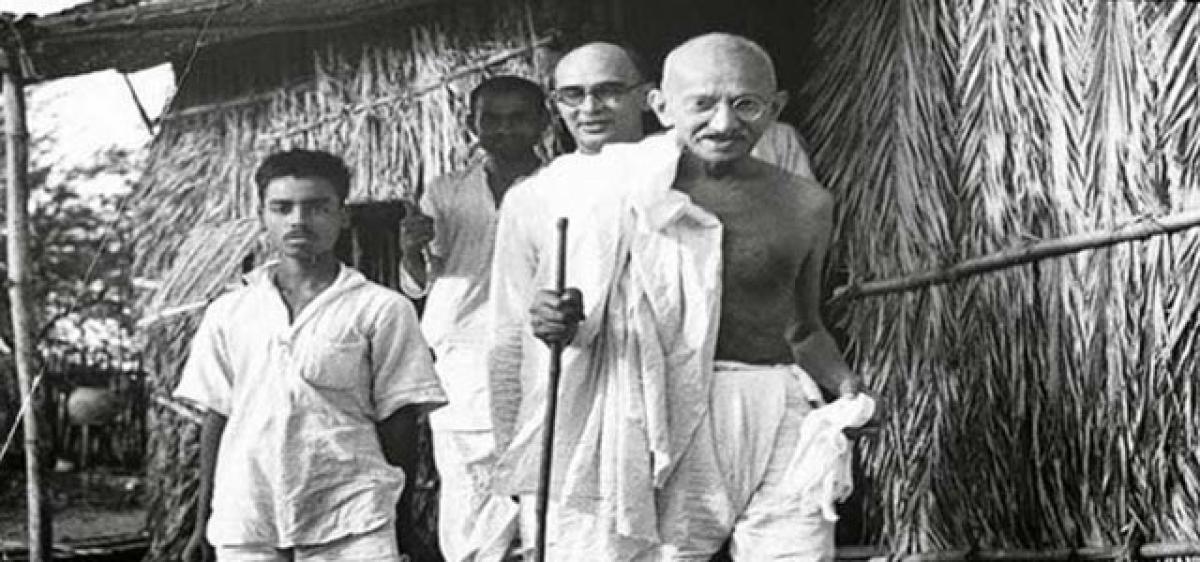

This is the centenary year of the Champaran Satyagraha (policy of passive political resistance) - the first experiment by Mahatma Gandhi of his epic philosophy. This tool was to become Gandhi’s most powerful armour and earned him a cherished and coveted place in the pantheon of world’s legendary leaders.

In Champaran’s centenary year, Indian farmers await another Gandhi

This is the centenary year of the Champaran Satyagraha (policy of passive political resistance) - the first experiment by Mahatma Gandhi of his epic philosophy. This tool was to become Gandhi’s most powerful armour and earned him a cherished and coveted place in the pantheon of world’s legendary leaders.

Gandhi launched his satyagraha in Champaran district on April 17, 1917. During the 31st session of the Congress in Lucknow in 1916, Gandhi met Raj Kumar Shukla, a representative of farmers from Champaran, who requested him to go and see for himself the miseries of the indigo ryots (tenant farmers) of Champaran. He responded immediately and among those he mobilised was Dr Rajendra Prasad, later to become independent India’s first President.

Gandhi arrived for the first time in Patna on April 10, 1917, and five days later, he reached Motihari, the district headquarters of Champaran, from Muzaffarpur. On April 17, he set off on his Champaran Satyagraha. No one could imagine that Gandhi’s visit would snowball into the first Satyagraha.

It was at Champaran that the transformation from Mohandas Gandhi to Mahatma Gandhi began. One of the most important outcomes of this movement was the enactment of Champaran Agrarian Act, which gave several concessions to farmers. Gandhi’s movement was a political campaign operating in a more hostile environment than today.

Yet it brought lasting reform without alienating the opposition. Gandhi used this technique for the first time and specifically for justice of farmers. Buoyed by its powerful moral impact, without any physical fallout, he made it his universal weapon for all crusades. Along with ahimsa (nonviolence), it forms the twin stand of the DNA of Gandhian philosophy.

Gandhian scholars and activists believe that the state of farmers in and around Champaran and other parts of the country now is no better than the condition of Indigo farmers in 1917, which had brought Gandhi to the State in the first place.

While indentured labour, which was one of the targets of Satyagraha, has been abolished many of the issues of farmers that Gandhi championed during the Satyagraha continue to bedevil farmers.The farmers desperately await another Gandhi for their redemption.

The roots of despair of Indian farmers have been well-researched and documented. They are a toxic blend of livelihoods drained away by spiraling debt and predatory moneylenders; soil tired on account of heavy doses of chemical fertiliser, crops and livestock destroyed by drought or unseasonable monsoon rains associated with climate change; plummeting water tables from relentless water mining; loss of agricultural land to development; collapse in cotton prices and growing expenses on genetic-engineered hybrid seeds; total breakdown of agricultural extension support and near absence of rural mental health services.

Despite their huge numbers small farmers are not a solidified block and have not articulated their political and negotiating power. According to Ashutosh Varshney, Professor of International Studies and the Social Sciences at Brown University, social divisions within the countryside have been the main reason why India’s rural voters have failed to push for policies that boost farm and rural incomes.

Varshney argues that their large size and heterogeneity limits their influence on public policy. Farmers’ refusal to give precedence to their economic interests over their other interests and loyalties (such as to castes and ethnic groups) have limited their influence over public policies.

Years of market-oriented reforms have unleashed a wave of capital and entrepreneurialism across India. But despite high-end sectors such as information technology making impressive strides and adulatory portrayals of India at home and abroad as an economic juggernaut, the benefits of reform have yet to extend to the hundreds of millions who toil on the land. The government has slashed or phased out subsidies for some crops, shredding a key safety net. The result is a growing social crisis.

Fueled by crushing debt for buying transgenic seeds, failing crops on account of the abuse of soil by fertilisers, squeezing of prices by big multinational and government indifference farmers are trekking to cities, where an equally cruel fate awaits them but they are saved the shame of humiliation in the eyes of their own fellow villagers.

A sense of deep despair runs through the lives of farmers. They have lost all hopes – and also the will to fight. Many of them are taking a permanent escape from this physical and emotional pain by ingesting deadly pesticides.

The government needs to revamp its extension services so that farmers have access to latest technology and field practices. The agricultural universities must be involved in creating tailored educational programmes that serve the diverse needs of India's huge rural population. Small farmers need to learn how to work with limited land areas in a productive and environmentally friendly way.

They need not only better plant species, but also up-to-date guidance on growing them. They don't need high-tech tractors controlled by satellites, but they do need access to regional databases that provide information on soil quality. They need access to affordable capital so that they don’t pile up unmanageable loads of debt.

An estimated 52 per cent of the country’s 90 million rural agricultural households have one debt or another. Agriculture’s share in the national economy has declined in recent decades, prompting banks to lend more to other productive economic sectors thanks to increased competition from private and foreign banks.

With institutional credit drying up for farmers, local harks have taken the place of banks and who charge an arm and a leg and are creating a debt-trap for the farmers, who rely on crop success –and prayers –for loan repayments. But a suicide does not absolve the rest of the family from paying back a loan. Unlike a bank loan which is squared by the government’s waiver package, the moneylender’s loan has to be atoned by the distraught family.

India’ first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said in 1947, “Everything can wait, but not agriculture.” But what India is witnessing is exactly the reverse. All the paths of Indian economy are surging ahead. Agriculture is the solitary one that is beating a path back in retreat.

By: Moin Qazi