How to bail out farming in fast-paced world

A farmer these days can engage in a dialogue with a group of agriculture scientists for a solution to the problem like pests infesting his crop, in real time, and online. Likewise, an importer of mangoes in Paris can conduct a visual inspection of the fruit while it is stocked in a container at airport in India and electronically complete the transaction with the producer. A group of farmers can hire a drone whose observations of the crops in their fields can be analysed, by an agriculture scientist hired by them, to decide upon nutrition, disease-control etc.

"Everything else can wait," said Jawaharlal Nehru in the early 1950s, "but not agriculture". Such was the overriding priority accorded to the all-important agriculture sector in the early days of our planned economic growth. In the aftermath of the Chinese war in 1960s, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri had emphasised national priorities with the catchy slogan "Jai Jawan-Jai Kisan".

In this daily (issue dated October 7, 2015), this columnist described challenges being faced by the farming community, and the agriculture sector, and made some suggestions. Though those issues have been around for over two decades, not much has changed. Agrarian distress persists. The contribution of the agriculture sector to the GDP remains unsatisfactory, transaction costs have not decreased, and capital formation remains low with decreasing public investment. The distressing phenomenon of farmers committing suicides continues. Therefore, some important issues relating to agriculture sector have been chosen for discussion this week.

The world has shrunk in size over the past century. Travel has become faster than ever before, and the IT revolution has made communications instantaneous. Exchange of ideas, information and news is taking place at, literally, the speed of light.

In 1919, Arthur Eddington and Frank Dyson organised an expedition to Sobral in Brazil and Principe in West Africa to establish the veracity of Einstein's general principle of relativity through measuring the precession in the perihelion of planet Mercury during a solar eclipse. News of the success of the experiment took months to reach Einstein. In the 1960s, it used to take two weeks for colour photograph to be printed and converted into positives; long-distance calls took hours to 'mature'; results of medical tests took days and sometimes, weeks before doctors could study them and decide on treatment. But not anymore. Tasks like the examination by a judge of an accused or the monitoring of the physical progress of work in progress in a project like a bridge under construction, can be done by videoconferencing and the facility of sending photographs through WhatsApp.

Such spectacular advances should have had their impact on the support systems which assist agriculture, (the 'big-five' being research, extension, financial services - credit and insurance - , meteorology and marketing).

In 1994, while in Israel, this columnist found that as much as 97.5% of the budget of the National Research Organisation (NRO - the counterpart of the ICAR) was driven by farmer demand, that is contract research. In India, it is not even the other way round!

A farmer these days, can engage in a dialogue with a group of agriculture scientists for a solution to the problem like pests infesting his crop, in real time, and online. Likewise, an importer of mangoes in Paris can conduct a visual inspection of the fruit while it is stocked in a container at airport in India and electronically complete the transaction with the producer. A group of farmers can hire a drone whose observations of the crops in their fields can be analysed, by an agriculture scientist hired by them, to decide upon nutrition, disease-control etc. The India Meteorological Department (IMD) sometimes predicts "normal" rainfall in June in a given area, (which can, theoretically, mean floods in a part thereof and drought conditions in the other potion). More accurate predictions in much smaller areas can be made with better use of modern technology and an expanded network.

Clearly the support systems of agriculture have a long way to go to successfully bridge the gap between the availability of their services and their accessibility and convert the cafeteria or supply approach into a demand driven syndrome.

There are, worldwide, around 360 Good Agricultural Practices (GAP)s listed internationally which the farmer is expected to comply with before his product is accepted in the international market. In India, the farmer has to follow around 90 GAPs. For that, he will need to do what is to be done. That is the job of extension, which can perform that function only after familiarising itself with the list of prescribed GAP. While each service has its own unique importance in the chain, extension is easily the critical input. To quote Dr MV Rao who was Additional Director General of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) (literally the father of the 'yellow' or oilseed revolution in the country), the country needs more "extension, extension, extension". Financial services such as banks and insurance providers also need to contemporise their practices. The flow of agricultural credit to the farmers through formal institutions is nowhere near what can be achieved, given determination and focus, and, of course, the supporting policy environment necessary to help bankers to maintain credit discipline and ethics. Their methods and procedures need improvement. Insurance is another area where coverage remains very poor and the efficacy of compensation largely well below par.

Many issues will need attention in the future. Agriculture research will, in the future, need to become solution–driven and, if possible, be of the adaptive type, rather than blue sky or fundamental variety. Research being largely a matter of academic pursuit, is not a weakness confined to the agriculture research system alone. In fact, this columnist, himself, has a Ph D in mathematics which, while undoubtedly, a result of original and authentic work, hardly can be said to have expanded the horizons of knowledge! Several innovative and interesting steps have been taken in the past both in the direction of improving the research and extension effort and also to combine them to good advantage. These include programmes such as the establishment of Krishi Vigyan Kendra and 'the lab to land' approach.

The experience with the green revolution of the 1960s is a clear indication of the resourcefulness, adaptability and openness to new ideas on the part of the Indian farmer. He only needs to be shown the way.

The first Green Revolution of Indian agriculture was largely the outcome of the use of hiding varieties of seeds, provision of major location facilities and the promotion of the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides. However, the vital imperatives of much-needed ever–green revolution (to use Dr MS Swaminathan's expression), – are yet to make a strong footprint in the emerging policy–environment, post the advent of the forces of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation. As a result, emerging challenges such as climate change which are causing demand-supply imbalances are not being addressed adequately.

Sweeping reforms are needed in the extant administrative and financial arrangement (in the Central and State governments) that fuel agricultural growth and development of agriculture. Importantly, the subsidies currently being extended will need to be rationalised in such a manner as to make them targeted, back-ended and transparent.

In the piece that appeared in this esteemed paper (referred to in an earlier paragraph), a case was made out for structural changes in the agricultural administration systems of the country both at the national and State levels. A paradigm shift was recommended, away from measuring production and productivity as the yardsticks of success of the agriculture departments to aiming at enhanced farm incomes. Changes suggested included the establishment of a Cabinet Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development headed by the Prime Minister at the national level, similar committees headed by the Chief Ministers at the State level and district level committees headed by the District Magistrates/Collectors. The committees were to be serviced respectively by MANAGE (the National Institute of Agricultural Extension Management), SAMETI (the State Agricultural Management and Extension Training Institute) at the State level and ATMA (the Agriculture Technology Management Agency) in the districts. State-of-the-art planning skills were also recommended to be created at the district level to feed into the abundant funds already made available already under the Rashtriya Krishi Vigyan Yojana (RKVY) at the State level. Several other related operational and administrative innovations were also part of that set of recommendations.

Needless to say, all the systematic reforms so far discussed will have the desired impact only if they are preceded by those reforms.

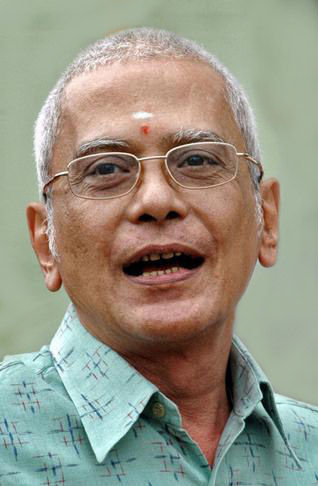

(The writer is former

Chief Secretary, Government of Andhra Pradesh)