Bharat Taxi Bets on the Amul Model to Rewrite India’s Ride-Hailing Story

Bharat Taxi aims to disrupt ride-hailing by adopting an Amul-style cooperative model that puts drivers, not corporations, in control.

Bharat Taxi is positioning itself as the “Amul of ride-hailing”, a comparison that carries weight in India’s economic imagination. Amul transformed millions of small dairy farmers into collective owners of a national brand. Bharat Taxi now wants to replicate that cooperative success in the gig economy, challenging established players like Uber, Ola, and Rapido by handing ownership back to drivers.

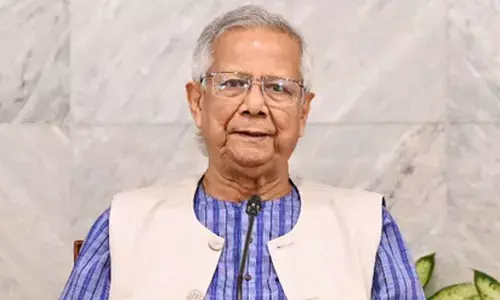

Set to launch nationwide on January 1, 2026, with pilots already running in select cities, Bharat Taxi is built on a simple idea: no profit-hungry corporate middleman. Instead, it operates as a driver-owned cooperative where thousands of drivers come together to run the service themselves. The platform is managed by Sahakar Taxi Cooperative Limited, based in New Delhi, and notably chaired by Jayen Mehta, the Managing Director of Amul. The initiative is backed by the Ministry of Cooperation and integrated with the National e-Governance Division (NeGD), lending institutional credibility.

Unlike conventional ride-hailing apps that take a 20–30 per cent cut from each trip, Bharat Taxi follows a zero-commission approach. Reports suggest drivers may retain anywhere between 80 to 100 per cent of their fares, though a small contribution will likely be pooled to cover operational costs. For drivers burdened by fuel expenses, vehicle EMIs, and platform commissions, this could mean significantly higher daily earnings. The interest is already visible, with more than 51,000 driver enrolments reported within just ten days of the announcement.

Drivers are not merely service providers on the app; they are stakeholders. The cooperative’s governing board is expected to include elected driver representatives, giving them a direct voice in decision-making. For passengers, Bharat Taxi promises relief from unpredictable surge pricing. Regular routes such as daily office commutes may cost roughly the same each day, rather than fluctuating wildly during peak hours or bad weather.

The bigger question is whether the cooperative model can scale in a technology-driven service like ride-hailing. Amul’s success rests on trust, volume, and sustainability rather than maximising profits. Bharat Taxi follows the same logic. It does not need to outperform global giants financially; it only needs to work better for drivers. If a driver earns ₹500 more per day and a passenger saves ₹250 by avoiding surge pricing, loyalty on both sides could follow.

On the technology front, Sahakar Taxi Cooperative has chosen a practical route. The Bharat Taxi app uses the same backend technology as the ONDC-backed Namma Yatri app, developed by Moving Tech Innovations. Early testing shows the app works largely as intended, though refinements are expected as it moves out of beta.

Still, challenges remain. Unlike Amul, where farmers produce milk and the cooperative handles distribution, in ride-hailing the “product” is the driver and the car. Human behaviour, road conditions, and dispute resolution add layers of complexity. Questions around accountability—when things go wrong on the road—will test the cooperative’s governance.

Global examples offer mixed lessons. New York’s Drivers Cooperative has shown that a driver-owned alternative can survive against Big Tech. On the other hand, Goa’s tightly controlled taxi ecosystem shows how collective power can also work against consumers.

Which path Bharat Taxi takes will only become clear after launch. For now, it represents a bold attempt to bring cooperative economics into India’s app-driven mobility landscape—an experiment rooted in trust, fairness, and shared ownership.